Alice Payne, Queensland University of Technology; Dean Brough, Queensland University of Technology, and Peter Musk, State Library of Queensland

Conventional leather is one of fashion’s most ubiquitous materials – but it is fraught with ethical and environmental issues. We have been growing vegan leather from kombucha tea since 2014 – and the results are promising.

Kombucha is a ferment made by adding a mixed symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast, (known as SCOBY) to sweetened tea. The bacteria acquire nutrients from the yeast, and grow a protective mass of cellulose monofibres, called a pellicle.

The pellicle (also called the mother) floats on the surface of the liquid, and will take the shape of its container. After a few weeks, when it has grown to a thickness of about 10mm, it can be harvested, washed (by hand or machine), oiled and air dried.

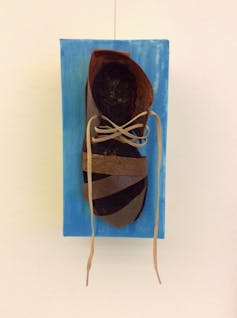

The material which results is a flexible, leathery sheet that can be cut, stitched, glued or woven. The pellicle dyes readily while still wet, and takes the shape of whatever supports it as it dries. Complex shapes can be formed by cutting the sheet into strips, and layering them over a form. As they dry, the wet strips fuse into a continuous sheet.

The technology of growing and using kombucha cellulose as vegan leather has been explored over the past few years through a collaboration between the Fashion department, Queensland University of Technology and scientists from The Edge, State Library of Queensland. They have trialled methods for preparation, treatment and manufacture of garments, shoes, jewellery and bags.

Just like animal based leathers, our leather-like items such as shoes and bags require reinforcing and finishing to increase durability. Shoe styles vary from casual slip-ons to more conceptual designs with handmade wooden heels and soles.

We have experimented with waxing the vegan leather to increase water resistance, laminating it to increase overall strength and wearability, and painting it with acrylics to dramatically change its appearance and improve longevity.

As a naturally sustainable material, kombucha leather has many advantages. Unlike the patternmaking process for traditional leather, which typically wastes 15% to 20% in the cutting due to garment pattern shapes, kombucha leather can be grown with zero waste, in tubs shaped as garment pattern pieces.

Can it work on a large scale?

But can kombucha be commercialized at a scale to be a viable vegan alternative to leather? There are two main barriers to overcome: the sweet but pungent aroma (familiar to any home brewer) and water absorption.

Like animal-based tanned leathers, kombucha leather is not waterproof. Rubbing in natural essential oils or beeswax as a sealant can address both scent and water resistance, although traces of the smell will remain.

These simple treatments make the material showerproof, but like leather, more work is required to make it truly impervious. Without a sealant, the kombucha could become sticky if worn in the rain. Full water resistance can be achieved if using acrylic or oil based sealers, but then the material is no longer safely biodegradable.

However, commercialization in the mass-market sense is only one avenue to explore. Like many other potentially disruptive technologies, production of kombucha is decentralised, democratised and personal. It gives people the means to make their own leather products on a small-scale.

Knowledge could be shared and grown across wide networks using available media, as parallel communities of tinkerers and makers connect. Free and open exchange of knowledge is a hallmark of these communities. Our project is only one of many such projects mushrooming globally – from trailblazer Suzanne Lee with her bio-couture jackets, to Sacha Laurin with her runway creations in California, to the ScobyTec start-up in Germany with prototype biker jackets incorporating wearable technology.

Looking to the future, kombucha cellulose may play a role as a mass-market alternative to leather. From the beginning of our project, sustainability and waste minimisation have been a priority. So treatments using artificial agents have been largely avoided.

The environmental ills of clothing production (waste generation, chemical toxicity, energy intensity) are rightly receiving increasing attention, and the search for sustainable materials is ramping up.

The world’s largest apparel brands are developing innovations in circular production methods, in which materials can be closed loop recycled, formed from pre-or post-consumer waste, or safely biodegraded at end-of-life – see PUMA’s cradle to cradle sneakers or Nike’s utilization of waste.

In addition, developing biotextiles has become fashionable, with novel biodegradable materials developed from waste pineapple leaf fibres (Piñatex™) and fungi, and textile dyes from algae garnering “likes” and shares on social media.

For now, kombucha growing provides local, individual makers with sustainable materials – and allows them to tap into the knowledge of a networked global community. This suggests a parallel fashion future in which makers grow their own garments, sharing the SCOBY locally, but ideas and instructions globally.

Download your instructions from here and try growing your own today.![]()

Alice Payne, Lecturer in Fashion, Queensland University of Technology, Queensland University of Technology; Dean Brough, Senior Fashion Studio Lecturer, Queensland University of Technology, and Peter Musk, Science Catalyst at The Edge, State Library of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.